An amazing aspect of the federal trial now underway against a Duplin County hog farm is the baffling reporting by the media, which has led to misinformation in the public about the case.

So let’s be very clear up front: If you have read any coverage of the ongoing nuisance trial involving Joey Carter’s Duplin County farm, you can be assured that it is not from any reporter who has watched the trial unfold.

That’s because none has.

The News & Observer last week described actual testimony from the courtroom as if the reporter were there – and yet no N&O reporter has ever appeared in the courtroom. Worse, what they wrote was flat wrong.

The Associated Press has briefly appeared, but no AP reporter has been present for the full examination of even a single witness. And yet, in one recent story, the AP filed a report about the testimony from plaintiff Elvis Williams – one of the two people for whom the lawsuit has been brought by a Texas lawyer.

Mr. Williams was on the stand for only about 45 minutes. Even then, the AP left in the middle of his testimony, sacrificing the opportunity to present a fair report about the claims at hand.

Further, no media was in the courtroom on Friday, when neighbors who live close to the Joey Carter farm testified about the actual conditions at the farm and its surroundings from decades of experience.

Much of the reporting has come from claims made in court documents before the trial began. As everyone should know, there is a big difference between claims and testimony – and this is true of both sides.

The media-fostered misinformation has led to a fundamental misunderstanding among many on the outside about a case that could have pivotal implications for the economy of North Carolina. The misunderstanding extends to some lawmakers, who debated and objected to a bill about nuisance cases and agricultural operations. Still, with support from town officials in eastern North Carolina and agricultural groups, the bill passed and is now on Gov. Roy Cooper’s desk.

Let me explain what’s happening in court, and why many across all of agriculture are concerned and supported the bill.

The case at hand involves two plaintiffs, Elvis and Vonnie Williams.

They are bringing a suit against the Joey Carter hog farm outside Beulaville in Duplin County.

Specifically, they seek money from Murphy Brown, a hog producing company that supplies the pigs to the Carter farm. They do not seek any fixes to the farm, and a negative verdict would almost certainly depopulate the farm of its livestock and wipe out something Joey Carter has spent his life building and operating with great care.

The Texas lawyer and his clients want the jury and the public to believe the farm is a legal nuisance, which means it allegedly interferes “unreasonably” and “substantially” with the use and enjoyment of the plaintiffs’ property.

Substantially interfering with someone’s property is not just a slight inconvenience. The claim has to rise to some level of significant annoyance or material discomfort.

Otherwise, we’d all have to live in bubbles where trains don’t blow horns, dogs don’t bark, trash trucks don’t arrive early, and there’s not any noise or odor from the paper mill, landfill, chicken farm, hog house, airport or, yes, even a restaurant or bar or baseball stadium. Ever lived next to an amusement park?

In the same way, “unreasonable interference” with someone’s property must involve activity that is excessive and inappropriate. In weighing that out, the jury must balance the interest of the plaintiff, the defendant and, yes, the community. A jury is supposed to consider such things as the suitability of the location of the farm, the nature and utility of the farm, and the character of the surroundings.

And most people would think both sides should be able to present their case.

One complaint of the pork industry is that the jury has been unable to even go visit the farm and see the character of the surroundings and smell for themselves the hog barns and the lagoons that treat the manure. Nor can the jury hear from an expert about odor studies near the farms because of a judicial ruling. Nor can the jury know that the lawsuit wasn’t the result of some unresolved complaint among neighbors – no, the lawyers swooped in and literally held gatherings encouraging people to sign up and win some money.

Now, what are the facts about this actual situation as told in the courtroom? Let’s take a look.

The lawsuit and the farm

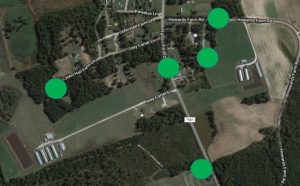

The two plaintiffs live in the general area where the red dot is shown above in this photo, with is about three-quarters of a mile across.

Their location is in there between Howard Farm Lane, John Hall Farm Lane and Turkey Farm Lane. That’s Turkey House Lane over on the far right.

Look up there at the top right. Those three barns are not the Joey Carter hog farm.

That was Joey Carter and his father’s turkey farm until they sold it. They also kept hogs on the ground there. At least two others operated it after them, but it’s no longer in use today.

The oldest part of Joey Carter’s current hog farm is actually just outside the frame, at the bottom left.

Joey Carter built that hog farm in 1985.

Mr. Williams moved in four years later, in 1989.

Mr. Williams told the courtroom that his ex-wife did all the looking for property back then before they bought any land.

The testimony was that he grew up in the area, and he went to high school with Joey Carter. His fulltime career was as a machine inspector at a nearby textile plant.

But he claimed not to know or not recall that the hog farm was there then.

And he told the courtroom that he bought his land, one acre for $5,000, from Joey Carter’s dad, a farmer with turkey houses and hogs on the ground and whose son was by then in the hog business for four years.

He said he didn’t get out of the car the one time he looked at the land, which was surrounded by soybeans, before he bought it for his home.

The record shows that Mr. Williams didn’t get a septic system for his land until a year later, in mid-1990. And so at some point after that he would have been able to live in his mobile home on the site, though memories on specifics were fuzzy.

Joey Carter built four new hog houses north of his existing farm in the early 1990s. In the frame above, they’re just outside it, at the top left.

Mr. Williams testified that he didn’t much notice the hog farms back then because he was inside all the time, generally helping to raise his children, or he was at work. He testified that he was a “loner,” and did not socialize with others in the neighborhood nor do much in the way of social gatherings.

It was a long time after he was there, he said, that he even knew there was a hog farm nearby.

At some point, Mr. Williams and his first wife divorced. In the settlement, they split the land 50-50. And he received the mobile home free and clear.

Now, the testimony showed that he also owned land nearby that was “family land,” adjoining his parents’ land. It was more than 3 acres. But he didn’t move away and put his mobile home there on his family land. Instead, he bought out his ex-wife’s share of his land near the hog farm and stayed put.

That was in the late 1990s.

Then, in 2007, he married Mrs. Williams. She owned her own home several miles away.

But, that year, she moved in with him – next to the hog farm. They’ve kept her former home as a rental.

She is the only other plaintiff in the ongoing trial, having moved near the farm some 25 years after they were fully operating.

When they were asked about their problems with the Joey Carter farm, they said that it smells at times. It’s not all the time, and it’s not always bad, they said. But there are times when there is an odor that keeps them inside, they said.

They said that Mr. Williams has added on a screened porch on the front side of his home to grill in, while he used to grill out back.

He said a truck that collects mortality on the farm bangs loudly some mornings. And he attributed flies at his home to the hogs.

But he sidestepped questions about the chicken coop and rooster in the yard directly behind him, as well as about the cows and horses that run on pasture much closer to his property than the hogs.

He was asked about what bothers him about the hog farm, and the answer was that he likes to sit on his porch and sometimes he doesn’t feel that he can because of the odor. Besides that, he doesn’t like hearing the truck bang on some mornings.

The plaintiffs make no health claims at all. And they do not claim their property value has been hurt by the farm. Both points are in contrast to widespread media reports.

Let’s take another look at the area, closer to the hog houses.

To make it all fit, this is a view from a different perspective – with north to the left. The plaintiffs’ property would be just off the frame, up at at the top.

At the trial, testimony from neighbors nearby, shown by the green dots, outlined decades of experience both before and after the farms. One man spoke of regularly jogging by the farms. Several said they have walked on the farm property. And some were from homes and property that directly border the fields where manure is applied as fertilizer.

What they said is that the farm simply doesn’t smell in any way that is offensive, and that most if not all the odor is contained to the area near the hog houses. They said that the farm does not interfere with nearby properties, not with flies or buzzards or trucks or odor or anything else that you might have read about.

They spoke of cookouts and children playing with the barns nearby and of hanging clothes on the lines and of good, country living next to a farm. A hog farm.

This was in direct contrast to the plaintiffs, who are farther away, and to the media narrative.

Some of those who live closest and testified to no problem with the farm were African-American – again, which is in contrast to the media’s attempts to report these cases as racial divides.

What these closer-in neighbors did say is that the claims in the lawsuit against Joey Carter’s farm “don’t make sense.” Those were the words of an African-American woman who is the closest and has lived there for 44 years.

Over the objections of the Texas lawyer, one neighbor said an “innocent” man should not face the chance of “going down” this way.

Which brings us to the bill that is now pending.

Why a Right to Farm matters

It would be natural to say, well, this is what a jury is for – to sort all this out and make a decision.

But that hasn’t been the intent of the state’s Right to Farm law for decades. The legislature has long wanted there to be a very high bar for someone to bring a nuisance lawsuit against a farm, and for good reason.

Farms like Joey Carter’s increasingly face encroachment as populations shift or, as in this case, new neighbors move in as time passes.

Lawmakers, then, have sought to strike a balance that ensures the state’s lawfully operating farms – with all the dust and noise and odors and machines and late-night harvesting and early-morning planting that go with them – can continue to produce. The reason is because we all need food and clothing and other agricultural products, and we want North Carolina farmers to continue to operate, responsibly.

In the case at hand, there has been no allegation of negligence and, in fact, Joey Carter has embraced new technologies and operates them well.

But a series of court rulings have undermined the state’s long-held intentions – rulings that allowed this case to proceed to an expensive trial with an uncertain outcome and with one side concerned it could not present all information to the jury.

For the fourth time since 1979, lawmakers want to make clear that it should be difficult to label the state’s agricultural and forestry operations as legal nuisances.

Certainly, neighbors can still sue, but the result shouldn’t be a monetary award that drives a legal farm out of business or causes agriculture to move to other states.

Farmers strive to be great neighbors, and they are. But farmers also worry about the weather and their crops and their animals and, more than ever now, lawsuits.

Joey Carter sits in a courtroom these days instead of working on his farm.

That shouldn’t be.

– Andy Curliss, CEO