With Hurricane Dorian approaching the East Coast, the North Carolina Pork Council is sharing the following information adapted from a recent article published in The Journal of Land Use and Environmental Law at Florida State University (Volume 34, No. 2).

In mid-September 2018, a powerful hurricane took direct aim at the coast of North Carolina. Before it even made landfall, activist groups that oppose modern livestock agriculture took aim at the state’s hog farms, generating and spreading inaccurate information and photos through mainstream and social media channels2. They predicted that the storm would unleash devastation on the environment in a region that includes the state’s largest pig-producing counties3.

Hurricane Florence, with winds that exceeded 140 mph and rainfall amounts as deep as a yard stick, delivered a punishing blow to North Carolina. But, in contrast to the predictions of the activist groups, hog farms weren’t the problem. Instead, what the storm revealed was an industry that embraces common-sense regulation, and continuously improves its farming practices and protects neighbors and the environment.

Clearing up misconceptions

Activists against animal agriculture use hurricanes to draw attention to the industry’s use of anaerobic lagoons – an EPA-approved treatment system also used by some municipalities and other businesses. The system is misunderstood by the public. An anaerobic lagoon allows a farmer to collect and store manure from barns within a containment basin, where beneficial bacteria break down and treat the manure5. This natural treatment process creates an organic fertilizer that is then applied to a crop at approved agronomic rates6.

There are approximately 3,300 active hog lagoons in North Carolina. The treatment lagoons are operated under a non-discharge permit, meaning that the manure can only be applied through the agronomic process.

More than 98 percent of the industry’s anerobic treatment lagoons did not have negative impacts from the two recent record-breaking storms: Matthew (2016) and Florence (2018).

North Carolina hog farmers have seen about 20 hurricanes over the past 20 years, and have gained a wealth of experience in preparing for storms. Additionally, more than 100 farms have been voluntarily closed in the flood zone as a result of a buyout program.

Farmers and the companies they grow pig for know what farms are at risk of flooding based on previous storms. As Hurricane Florence moved toward North Carolina last year, more than 20,000 animals were moved from flood-prone areas, and more were moved during and in the aftermath of the storm. Losses of animals on hog farms were isolated, and no single barn lost all of its animals. Many farmers relied on portable generators to keep the fans and feed running in the buildings. Feed delivery was difficult in areas impacted by flooding. Even farms that weren’t flooded were in some cases marooned by flooding around them. In the worst hit areas, animal feed was delivered by boat.

And the lagoons? Most of them—more than 98 percent—experienced minimal impact. The summer of 2018 was dry, and lagoons were well-managed heading into September.

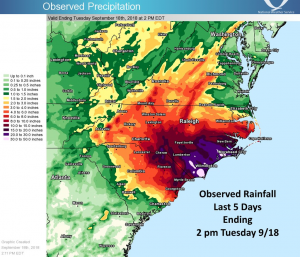

Hurricane Florence crawled for three days along the border of North Carolina and South Carolina, dumping an estimated 8 trillion gallons of rainwater on the state, and 11 trillion gallons in the region7. The storm measured in some locations as a 1,000-year event.8 The flooding that followed swelled rivers to record levels9. Many rivers remained at major flood stage nearly two weeks after the storm made landfall.

The record rains from Hurricane Florence impacted six lagoons with some form of structural damage to a containment wall, ranging from two instances where the lagoon was fully breached and released liquid contents (post-storm assessments show solids remaining) to other instances of “cracking” in the dike wall or less significant impacts. On twenty-eight farms, the lagoons filled up with the rainwater to the point that some liquid overflowed – mostly rainwater.

Context is crucial. The amount of rain that fell is understandably incomprehensible to an ordinary person. The rainfall amount equals nearly 4 billion gallons of water for every hog farm in North Carolina.

Studies after Hurricane Floyd in 1999, Hurricane Matthew in 2016 and Hurricane Florence in 2018 did not attribute impacts to the environment from hog farms. After Floyd, for example, widespread predictions of large fish kills caused by a variety of pollutants, including hog farms, were made. But they were proven to be incorrect.

“(T)he massive fish kills never happened,” one post-storm assessment concluded, “and in fact, the shrimp fishery had its best year since the state began keeping such records in 1972.”

After historic Hurricane Matthew in 2016, the NC Department of Environmental Quality conducted multiple rounds of surveys and sampling at multiple sites. NC DEQ concluded:

After reviewing the data collected, and comparing that to precipitation amounts, river levels and known areas of flooding, the overall impacts of Hurricane Matthew on surface water quality were initially minimal and temporary, and the long-term effects appear to be similar to previous storms and long term historical conditions. While many eastern North Carolina areas were inundated by floodwaters and incidents of spills, breaches or waste facility shutdowns were reported, the amount of water discharged into the river basins resulted in a diluting effect, which primarily resulted in lower than normal concentrations of various pollutants.

The human waste problem

Studies have concluded that human waste, in flooding events, is far more concerning than livestock waste for its potential effect on human health10. In contrast to hog farms, municipal waste plants operate under a permit that allows discharge into rivers and streams and often discharge raw human sewage directly into the waters of the state. These circumstances are the result of sanitary sewer overflows or direct bypasses of the treatment system itself11 in both heavy rain events and more significant storms12.

It is generally expected that there will be a discharge from such systems in the area impacted by the hurricane. During Florence, NC DEQ reported that more than 200 wastewater treatment systems across the state were compromised, releasing at least 121 million gallons of sewage that flowed into streets, fields and waterways13.

In Matthew in 2016, about 15 treatment lagoons were impacted. In contrast, the municipal systems experienced discharges of approximately 150 million gallons of raw sewage to the surface waters of the state14.

While it is common for municipal waste to be discharged during a typical summer thunderstorm, it is not a certainty that a hog farm lagoon will release any contents into the waters of the state during a hurricane. By design and by law, farmers must maintain a “freeboard” of roughly 19 inches, precisely to protect the structural integrity of the lagoon and to absorb significant rain events. However, in practice, lagoons are managed much more conservatively, with freeboard levels of up to double the requirement heading into hurricane season.

This is why, in the aftermath of Florence, NC DEQ Secretary Michael Regan said: “We are really focused on our wastewater treatment facilities because there are probably orders of magnitude more human waste that has escaped these wastewater treatment facilities than what has escaped these hog lagoons15.”

In a briefing to state lawmakers, the director of the NC DEQ Division of Water Resources likewise emphasized that impacts from swine farm lagoons were minimal, characterizing discharges as consisting of mostly water from the storm while also emphasizing the enormous amount of rainwater that fell.

“I am not sure why there is so much focus (on animal facilities),” division director Jim Gregson told lawmakers in a November 2018 briefing. “Looks bad, but primarily what you’re seeing on inundated farms is storm water.”

The positive outcome for the farms under the severe stress of a record-breaking hurricane illustrates a disconnect between experts who have conducted evaluations, and the activist groups and mass media, which have tended to ignore science or offer distortions in advancing political goals and outcomes. It is instructive, then, to also understand that the North Carolina pork industry has, indeed, made great strides in protecting animals, the community and the environment in the face of hurricanes in the past 20 years.

Hurricane Florence’s agricultural impact

Hurricane Florence caused $17 billion in damage in North Carolina and is responsible for the deaths of 48 people. More than 74,500 structures were flooded, 1,100 roads and highways were closed or impassable, and more than 2,200 people were rescued or evacuated16. Large swaths of major cities and towns—and all that was in them—were inundated. Approximately 140,000 North Carolinians registered for disaster aid. FEMA confirmed at least 10 dams and levees breached in the Carolinas17. Across other sectors of agriculture, the damage was profound, with possibly more than $1 billion in reported crop losses17.