On July 4, 1776, the Continental Congress adopted the Declaration of Independence, an enduring statement of freedom in the long Revolution that created our United States of America.

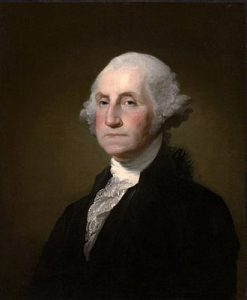

It was a farmer, George Washington, who led our army in that fight from tyranny.

If you look, Washington’s records reflect a significant reliance on hogs and pigs, both as a general in feeding his army and personally as a farmer at his home, Mount Vernon.

When Washington crossed the Delaware River, for example, with a hungry army in the surprise Christmas attack of 1776, it was after a scout had provided information about the stores of pork across the river in Trenton. The army secured those stores immediately after victory.

Indeed, throughout the war, soldiers survived on rations of pork. When supplies ran low, generals wrote directly to Washington seeking more pork for eager soldiers.

Once, in 1780, the army ordered about 400 barrels of pork and 200 barrels of beef – with the message “it is truly distressing to us to inform your excellency that the supply of meat will be totally exhausted on Friday next at the farthest.”

At his Mount Vernon home, according to logs and inventories, Washington kept innumerable hogs, processing them for meats and other products, including ham, “salted pork,” sausage, bacon, scrapple, chitterlings and lard. He built a smokehouse near his residence.

A view inside the smokehouse at Mount Vernon, the home of George Washington and, also, plenty of hogs and pigs.

In late 1785, two years after the Revolution was won, the records show that 128 hogs were slaughtered at Mount Vernon, yielding more than 17,000 pounds of pork.

Washington gifted 500 pounds of the pork each to a servant and a carpenter. Several farm overseers collectively received another 1,000 pounds.

The balance went to the Washington family and his servants and, in Washington’s words, “the poor who are distressed for it,” according to the excellent book by Alan and Donna Jean Fusonie, “George Washington – Pioneer Farmer.”

In 1792, while serving as our first president, Washington “introduced the spirit of new husbandry” into his hog-raising practices at Mount Vernon.

The president directed “his farm manager to construct closed pens with plank floors, a roof, water, and good troughs for feeding and fattening,” the Fusonies write.

The confinements served Washington’s hog farming well.

In his later years, Washington “seems to have taken more interest in his pigs,” writes Paul Haworth in “George Washington: Farmer.”

In the late 1790s, Washington built a distillery and made whiskey.

The purpose was both for revenue from the sale of spirits and “fattening hogs” on the leftover corn cobs and mash.

New hog pens were constructed at the distillery, as well.

A visitor stayed at Mount Vernon in 1798. Writing home, he commented on Washington’s enterprise, which included experimentation with different swine breeds.

The operation, he wrote, offers “the most delicate and the most succulent feed for pigs.”

“(They) are so excessively bulky,” the visitor wrote of Washington’s hogs at the distillery, “that they can hardly drag their big bellies on the ground.”

The year before his death, Washington made a will. He listed among his possessions a “large stock of hogs, the precise number unknown.”

And then he was gone, eulogized as “first in war, first in peace and first in the hearts of his countrymen.”

On this Independence Day, we reflect on our founding and our freedoms, most of all.

But we also reflect on the importance of agriculture in securing peace and then, just as importantly, providing for our continued prosperity.

– Andy Curliss, CEO